Executive summary

Militaries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) spend a lot on defence, yet their defence contracting is relatively undeveloped. Most spending comes through traditional, transactional contracts, which are easy to create and function well enough when requirements are clear and customer–supplier relationships are uncomplicated. However, these basic contracts do not operate well under the conditions common to the modern defence sector. Such contracts offer less value for money than alternatives. They are insufficiently flexible when requirements are more complex, suppliers have little competition, and risks are high or unavoidably shared. Under such circumstances, closer customer–supplier relationships, established through more-advanced defence contracting structures, prove to be far more advantageous.

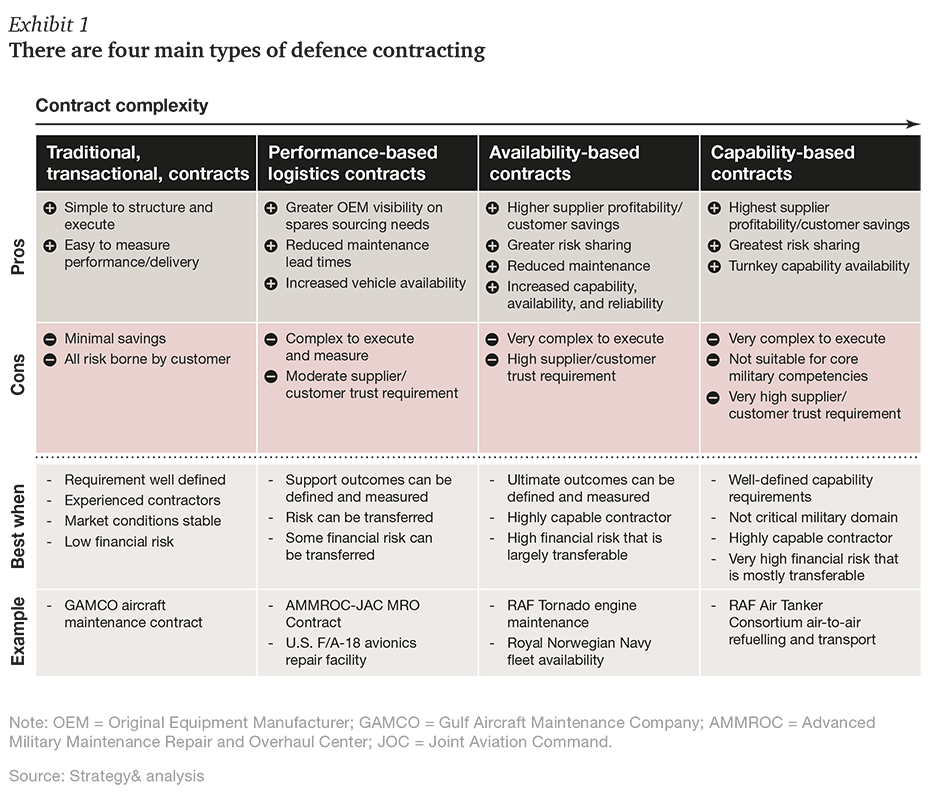

As an alternative to traditional, transactional contracts, there are three types of advanced defence contracts, each of which is more mature and complex than the previous: performance-based logistics (PBL) contracts, availability-based contracts, and capability-based contracts.

Advanced defence contracting models are more challenging to produce and manage, often requiring behavioural and cultural changes from both buyers and suppliers. However, these advanced arrangements offer significant advantages. By enabling closer partnerships among customers and suppliers, advanced contracts can deliver reliability and availability improvements of more than 20 percent, customer cost savings of 15 percent to 20 percent, and higher profit margins for suppliers. They also lay the groundwork for positive economic development by boosting the network of defence suppliers in the region.

The defence contracting landscape

Modern defence contracting offers both advanced and emerging militaries a range of options to suit the needs of various stakeholders (such as governments, armed forces, and suppliers) and situations. Broadly, these options consist of four basic contract types, each with varying levels of maturity and complexity (see Exhibit 1).

Traditional, transactional contracts

In traditional, transactional defence contracts, suppliers provide stipulated goods or services at prices that they agree in advance with customers. This is the most common type of contract employed by most MENA militaries. It is straightforward to create and administer, and allows customers to manage relationships at a distance.

Transactional contracts, however, have clear shortcomings. Customers shoulder most of the risk. Consequently, they tend to take an adversarial approach to ensuring compliance by their suppliers. For their part, the suppliers have to contend with the comparatively lower margins of these simple contracts. To cope with these unappealing margins, suppliers often improve profitability by offering lower levels of service. In extreme cases, this can lead to disputes involving situations that contracts have not stipulated in advance.

Performance-based logistics (PBL) contracts PBL contracts tie supplier remuneration to measurable key performance indicators (KPIs) such as speed of service, cost effectiveness, and the number of repeat repairs. The targets ensure that suppliers deliver high service levels, and incentivize contractors to render services at, or above, specification. In this way, PBL contracts introduce a degree of risk-sharing and improved commercial terms for suppliers. The U.S. pioneered PBL contracts after the Cold War to improve readiness and reduce logistics spend.1 The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) today uses PBL-based contracts for most of its purchasing.2

PBL contracts are, however, more complex to administer properly. Responsibility for the primary desired outcome, military readiness, remains chiefly with the customer. If contracts are not properly structured, they can include KPIs that are difficult to measure or do not correspond to improved readiness, which leads to misaligned incentives between the two sides. In other cases, militaries can enforce process- or cost-based KPIs to a degree that actually harms long-term readiness. For example, if a military imposes a set cost-per-flying-hour for air maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) services without factoring in fixed costs for the supplier, then a reduction in the flight hours could put undue financial pressure on the supplier. Indeed, early attempts to institute PBLs in some MENA countries, such as in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, 3 have led to precisely these kinds of issues.

Availability-based contracts

Availability-based contracting involves more shared responsibilities and allows for a better allocation of risks to the party best placed to bear them. It is more akin to a partnership than transactional or PBL contracting. Availability-based contracting evolved from PBLs during the 2000s, particularly in the U.K. and other European countries, where defence ministries faced stiffer budgetary pressures than their U.S. counterpart.

For example, an availability contract may allow customers to purchase a certain number of “flying hours” whereby suppliers promise to ensure aircraft availability for the stipulated number of hours, whatever the cost. Availability contracting tends to produce better working practices and results in a higher quality of maintenance because suppliers have an incentive to deliver and take responsibility for the output. Their margin is dependent on how seldom repairs need to be performed, rather than how frequently.4 Customers, meanwhile, can reduce their service logistics footprint.

European militaries offer several examples of successful availability-based contracting relationships. In the U.K., a Royal Air Force contract with Rolls Royce for the maintenance and upgrade of Tornado jet engines resulted in a 35 percent reduction in the overall number of repairs required.5 Similarly, an availability contract to service the U.K.’s Harrier jump jets resulted in savings of more than £100 million (US$126 million) over a five-year period and a 44 percent reduction in the cost per flying hour.6

In a more extreme example, the Norwegian navy entered into an advanced availability contract with Spanish shipbuilding firm Navantia (formerly IZAR) to provide Norway with its Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates in 2005. Navantia owned the vessels, maintained responsibility for their operational readiness, and even partially crewed the vessels under the command of Norwegian sailors.7

Availability-based contracting depends upon high levels of trust between supplier and customer, usually through long-term arrangements, sometimes in excess of 20 years. These contracts also work better when contractors own key parts of the value chain, such as the sourcing and management of spare parts.8 The customer transfers a degree of responsibility and financial risk to the supplier, but needs to ensure quality control throughout the process.

Availability-based contracting involves more shared responsibilities and allows for a better allocation of risks to the party best placed to bear them.

Capability-based contracting

In capability-based contracts, the supplier provides all aspects of an end-to-end capability normally handled by the customer. Capability-based contracts tend to be the most lucrative for suppliers and offer customers the greatest opportunity to rationalize their uniformed logistics footprint and costs. This is the most advanced form of defence contracts.

The complexity and degree of trust required to execute successfully such typically long-term contracts means they will be restricted to only the most capable of suppliers with reputations to match. In 2008, AirTanker, an Airbus-led consortium (previously known as EADS), won a £13 billion ($16 billion), 27-year contract with the U.K. Ministry of Defence to provide the RAF with mid-air refuelling and air transport services.9 The consortium will invest £2.5 billion ($3.2 billion) to create the fleet, underscoring the need for a long-term contract given that the supplier is taking responsibility for everything from infrastructure and ground services to fleet operations and pilot training.10

Capability-based contracts tend to be the most lucrative for suppliers and offer customers the greatest opportunity to rationalize their uniformed logistics footprint and costs.

Conclusion

The future of military readiness in the MENA region lies in advanced contracting and partnerships between the defence industry and the region’s armed forces. With typical reliability and availability gains of over 20 percent and cost reductions of 15 percent to 20 percent, the value at stake is clear enough to justify that military and government policymakers invest the effort necessary to transform legacy attitudes and procurement cultures.

Aligning defence suppliers and customers in strategic partnership roles will lead to improved military readiness, manpower allocations, cost savings, and national economic development. Advanced contracts are not a panacea for defence procurement. They will not remedy poor planning, a lack of funding, or inadequate leadership, and they will not deliver results overnight. However, a shift to properly structured advanced contracts would represent a step-change in the maturity of defence procurement in the MENA region, and the ultimate impact on military readiness promises to be significant.

1“Availability Contracting – Making Defence Procurement Smarter,” Defense-Aerospace.com, March 28, 2006 (http://www.defense-aerospace. com/article-view/feature/67702/the-growing-acceptance-of-availability-contracting.html).

2Ibid.

3The Gulf Cooperation Council countries are Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

4Availability Contracting – Making Defence Procurement Smarter,” Defense-Aerospace.com, March 28, 2006 (http://www.defense-aerospace. com/article-view/feature/67702/the-growing-acceptance-of-availability-contracting.html).

5Ibid.

6Jacques S. Gansler, William Lucyshyn, and Lisa H. Harrington, “An Analysis of Through-Life Support - Capability Management at the U.K.’s Ministry of Defense,” Center for Public Policy and Private Enterprise, University of Maryland, June 2012 (https://www.dau.mil/cop/pbl/ DAU%20Sponsored%20Documents/UMD%20FINAL%20Report%20 LMCO%20An%20Analysis%20of%20Through%20Life%20Support%20 Capability%20Management%20at%20the%20UK%20s%20Ministry%20 of%20Defense%20June%202012.pdf).

7Availability Contracting – Making Defence Procurement Smarter,” Defense-Aerospace.com, March 28, 2006 (http://www.defense-aerospace. com/article-view/feature/67702/the-growing-acceptance-of-availability-contracting.html).

8Jacques S. Gansler, William Lucyshyn, and Lisa H. Harrington, “An Analysis of Through-Life Support - Capability Management at the U.K.’s Ministry of Defense,” Center for Public Policy and Private Enterprise, University of Maryland, June 2012 (https://www.dau.mil/cop/pbl/ DAU%20Sponsored%20Documents/UMD%20FINAL%20Report%20 LMCO%20An%20Analysis%20of%20Through%20Life%20Support%20 Capability%20Management%20at%20the%20UK%20s%20Ministry%20 of%20Defense%20June%202012.pdf).

9“EADS-led AirTanker Consortium Signs 27 Year Air Refuelling Contract with the U.K. Ministry of Defence,” Defense-Aerospace.com, March 27, 2008 (http://www.defense-aerospace.com/article-view/release/92623/industry-partners-detail-role-in-raf-air-tanker-contract.html).

10Ibid.

Contact us

Menu